Web Components 101

2022-03-07 - Bradley Leonard

Web components

You may have heard of components in the past and that’s because it’s not a new concept. Components have been used across many web frameworks as a way to divide pieces of the frontend into re-usable chunks of code. Web components are no different, they make use of native web technologies to encapsulate logic into a re-usable and maintainable unit of code so that you can implement framework agnostic components.

Web components can be coded using plain js, HTML and CSS but there are plenty of libraries that aim to make it easier to write them. A good comparison of web component libraries can be found here. We are going to focus on plain old native versions rather than using a library. The technologies behind web components can primarily be broken down into 3 parts that we will cover in this 101 lesson. These parts are Custom Elements, The Shadow Dom and HTML Templates.

For this demo, we are going to create a web component that shows a lightbulb.

Custom elements

Normally HTML exposes a number of elements for us to play with. You might be familiar with a bunch of them like p, h1, div, etc… as they come built in with HTML and modern browsers. Custom elements are exactly like those built in elements, except we get to define their behaviour. A custom element only requires two files. (One if you’re talking about the custom element itself, the other is to test) The first file we will look at is the HTML file we use for testing the component.

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Web Components 101</title>

</head>

<body>

<script src="lightbulb.js"></script>

<lightbulb-component></lightbulb-component>

</body>

</html>Most of this file is a pretty standard HTML template, with a head and body. The two lines of interest are in the body itself. The script tag is how we import the custom element as this lets the browser know where to find the code for the custom element. The second line of importance is the lightbulb-component tag itself. This is our custom component! It is responsible for actually displaying our component in the DOM. To look at what is in our component, we will look at the second file: the javascript.

class Lightbulb extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

}

connectedCallback() {

this.innerHTML = "This is our Lightbulb component";

}

}

window.customElements.define("lightbulb-component", Lightbulb);The js isn’t that much more complicated either. At a high level, the file is broken down into two pieces. The first piece is the Custom Element js class and the other being the Custom Element definition. Looking at the js class itself, we can see that it extends the HTMLElement class. This is the base class for all elements which means if you want a starting point for building off an existing element like a p tag, you could do so using the HTMLPElemnt.

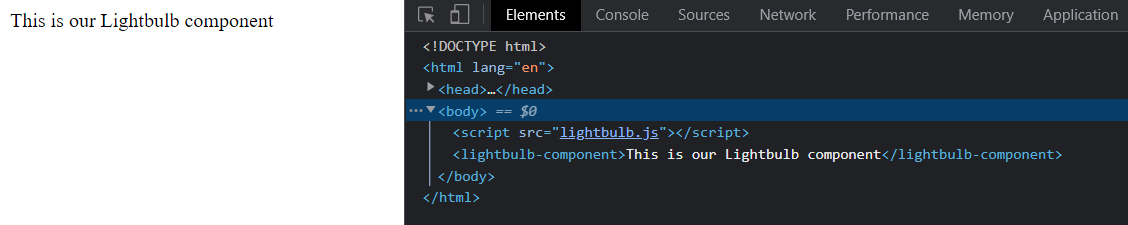

Looking inside the class, every custom element needs a constructor that calls super. This allows the element to set itself up. We have one other method connectedCallback This is a lifecycle method and it triggers when the Custom Element connects to the DOM. Since we have access to the DOM in this method, this is where we can set the content of our web component. Since we want to start small we will just set some text for now.

Now that we are done the class, we can focus on the definition. The definition is pretty simple, the first argument being the name of the web component that we will call on in the HTML. One thing to note about the naming is that you have to have a ’-’ in the name or the component will not be recognized. The second argument is the class that the element is going to use. In our case that is the class that we previously defined.

And voila! If you open the html file on a browser you can see our custom element displaying the text we gave it. This is just the start to web components, now we can start adding some more functionality.

Lightbulb Custom Component

The shadow DOM

We know the DOM as a tree of elements that describe the makeup of a web page, but what if I told you the DOM had a darker more secretive cousin? That cousin is of course the Shadow DOM! The Shadow DOM is like the normal DOM in most ways, except a Shadow DOM belongs to a certain element and encasulates that element’s contents.

You can think of it much like an apple. The inner contents of an apple are protected by it’s skin. A Shadow DOM isolates the inner makeup of a component. The benefit about this behavior is that the content of the Shadow DOM can be made inacessible to actors outside of the element and pieces like CSS are scoped so that they are unaffected by outer styles. No more guessing which important! is more important than other importants!

Since the HTML file didn’t really change for the introduction of the Shadow DOM, we will just take a look at the updated js.

class Lightbulb extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

const shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ mode: "open" });

shadowRoot.innerHTML = `

<svg style="width: 24px; height: 24px" viewBox="0 0 24 24">

<path

fill="#FEE227"

d="M12,2A7,7 0 0,0 5,9C5,11.38 6.19,13.47 8,14.74V17A1,1 0 0,0 9,18H15A1,1 0 0,0 16,17V14.74C17.81,13.47 19,11.38 19,9A7,7 0 0,0 12,2M9,21A1,1 0 0,0 10,22H14A1,1 0 0,0 15,21V20H9V21Z"

/>

</svg>

`;

}

}

window.customElements.define("lightbulb-component", Lightbulb);We added and removed some lines so lets go in order and talk about each one. The class itself and the constructor with super hasn’t changed. We did add 2 lines here. The first line creates the Shadow Root, which is just the root of the Shadow DOM. Since we are calling attachShadow on this, we are attaching the Shadow Root to the Custom Element itself. The other thing to note is that we are attaching the root in open mode. All this mode does is allows the Shadow DOM to be accessed by js outside of the element. If it were set to closed, that access would be unavailable.

Since we initialized the Shadow Root into a variable, we will then use that variable to set the contents of the Custom Element. In the first part, we set the content of the element in the connectedCallback because we needed the element to wait for a time in it’s lifecycle where it could attach to the DOM. Since the Shadow DOM is internal we don’t need that lifecycle hook anymore and can change the contents in the constructor. Since text is boring I’ve swapped the This is our Lightbulb component text for an SVG of a lightbulb. If you want to learn more about SVGs, check out my other blog post on the topic. Finally, nothing has changed with our definition, so we are done!

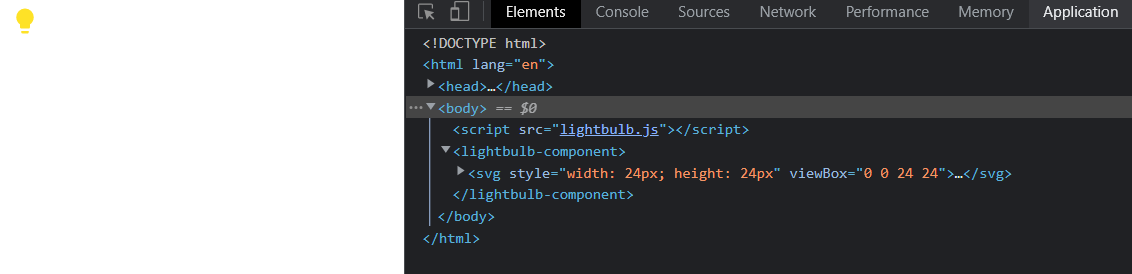

If we took a look at the Custom Element before we implemented the Shadow DOM, we would see the SVG contents of the element plainly in the DOM.

No Shadow DOM

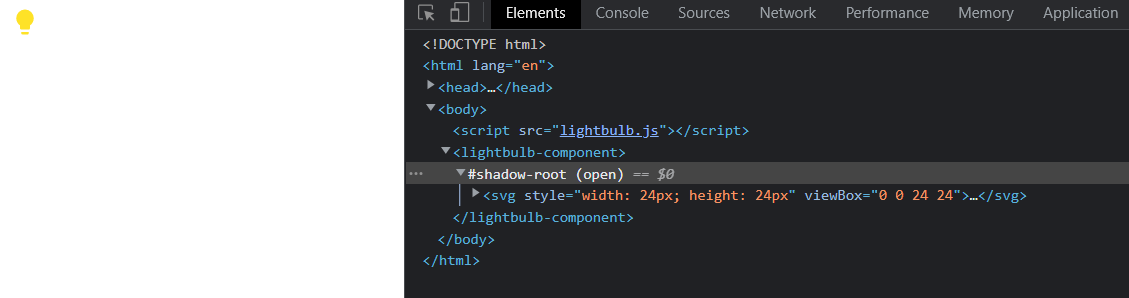

When we implement the Shadow DOM, you can see a distinct difference in how the lightbulb component is laid out. Since the Shadow DOM is in open mode, we can see and access all the inner contents. The SVG is now contained INSIDE the Shadow Root.

Shadow DOM

HTML templates and slots

The third technology to note is HTML templates. Templates are a HTML tag that doesn’t display content on a page but is used to “template” reusable pieces of UI. Since the templates introduce UI elements to the component, we will also introduce slots in this section to show how you can replace pieces of the UI. Let’s dive into the js again.

const template = document.createElement("template");

template.innerHTML = `

<style>

.icon {

width: 24px;

height: 24px

}

</style>

<slot name="svg">

<svg class="icon" viewBox="0 0 24 24">

<path

fill="#FEE227"

d="M12,2A7,7 0 0,0 5,9C5,11.38 6.19,13.47 8,14.74V17A1,1 0 0,0 9,18H15A1,1 0 0,0 16,17V14.74C17.81,13.47 19,11.38 19,9A7,7 0 0,0 12,2M9,21A1,1 0 0,0 10,22H14A1,1 0 0,0 15,21V20H9V21Z"

/>

</svg>

</slot>

`;

class Lightbulb extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super().attachShadow({ mode: "open" }).append(template.content.cloneNode(true));

}

}

window.customElements.define("lightbulb-component", Lightbulb);While we can use a template from outside of our component, from the DOM or an exported file for example, a common practice is to include the template inside of the component to have all of the code encapsulated in one place. We first create a template element in the document and then assign it’s innerHTML the contents that we want to display.

You’ll notice in this iteration we’ve even included a style tag. Since we are using the Shadow DOM, this style will not be affected by styles outside of the web component. For example if the “icon” class was defined in an external stylesheet and had a bigger width and height, that would not affect our component because the Shadow DOM scopes CSS. We’ve also surrounded the svg tag with a slot. This slot is given the name of svg and will be talked about more in a bit.

The rest of the code is the same in the file except for in the constructor. I’ve gone and cleaned up the constructor by making each piece a chain of the next. super returns a reference to the class, which is needed to attach the Shadow Root. The Shadow Root is then used to append the content, so chaining cleans up everything nicely.

The one line we haven’t seen up to this point is the template.content.clonedNode(true). This is getting the template we defined earlier in the file, grabing its content and copying it as a node to the Shadow Root. The reason we need to deep clone the content is that if we just used template.content it would actually “move” the template to be used in the Shadow Root. This would mean that you wouldn’t be able to make multiple instances of the web component and so a deep clone is used instead to allow reuse.

What if we wanted to swap our lightbulb SVG for nature’s lightbulb, LIGHTNING? Thats where slots come in. Slots allow us to make our components more flexible by swapping out content passed in by the regular DOM as a child of the component. Let’s look at what that looks like with the HTML.

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Web Components 101</title>

</head>

<body>

<script src="lightbulb.js"></script>

<lightbulb-component></lightbulb-component>

<lightbulb-component>

<svg slot="svg" style="width: 24px; height: 24px" viewBox="0 0 24 24">

<path fill="#FEE227" d="M7,2V13H10V22L17,10H13L17,2H7Z" />

</svg>

</lightbulb-component>

</body>

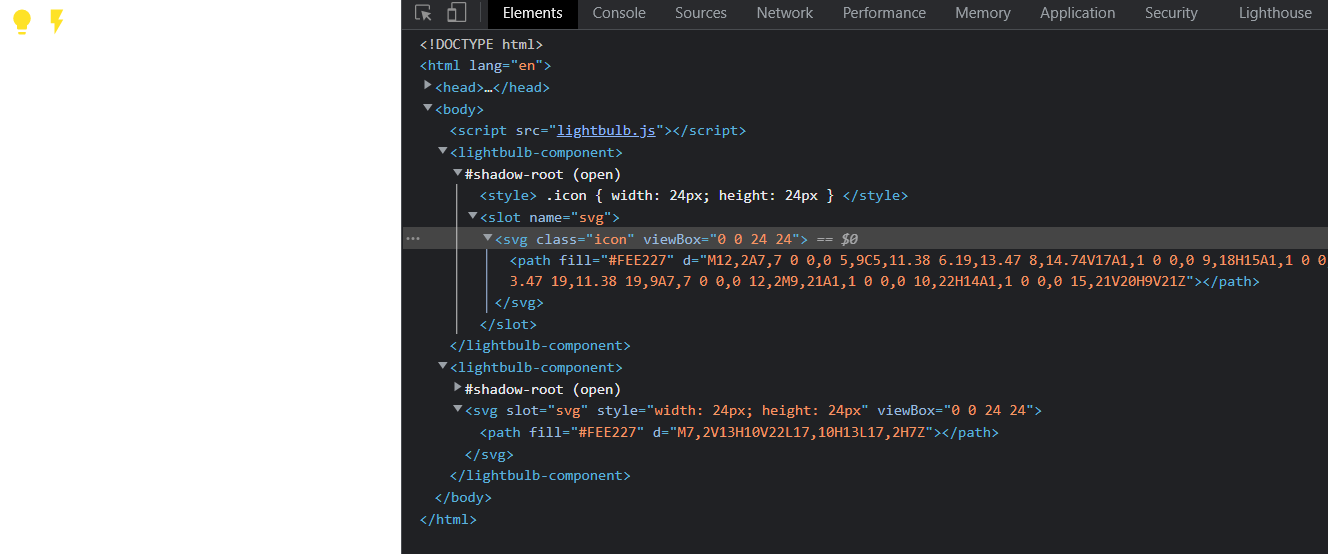

</html>As you can see we now have two instances of the lightbulb component. The first one doesn’t make any changes to the underlying component and as such shows up as the original lightbulb. The second instance is a little different however, it has it’s own svg of a lightning bolt which was given the slot svg. In the background as the element is being rendered, the slot with the same name of svg on the web component side is replaced by this svg. The results of this page can be seen below. We see that the slots allow all the functionality of the original web component, but taking advantage of the new content.

Lightbulb component using slots

Recap

You have sucessfully combined the 3 technologies to make a web component! Well done! While we only scratched the surface when it comes to web components and their utility, you now know enough to start exploring on your own. There is plenty more to learn, like adding js functionality to your components, styling, attributes and so much more. These components are a great way to add flair into any website and you’re bound to see them everywhere if you look close enough.